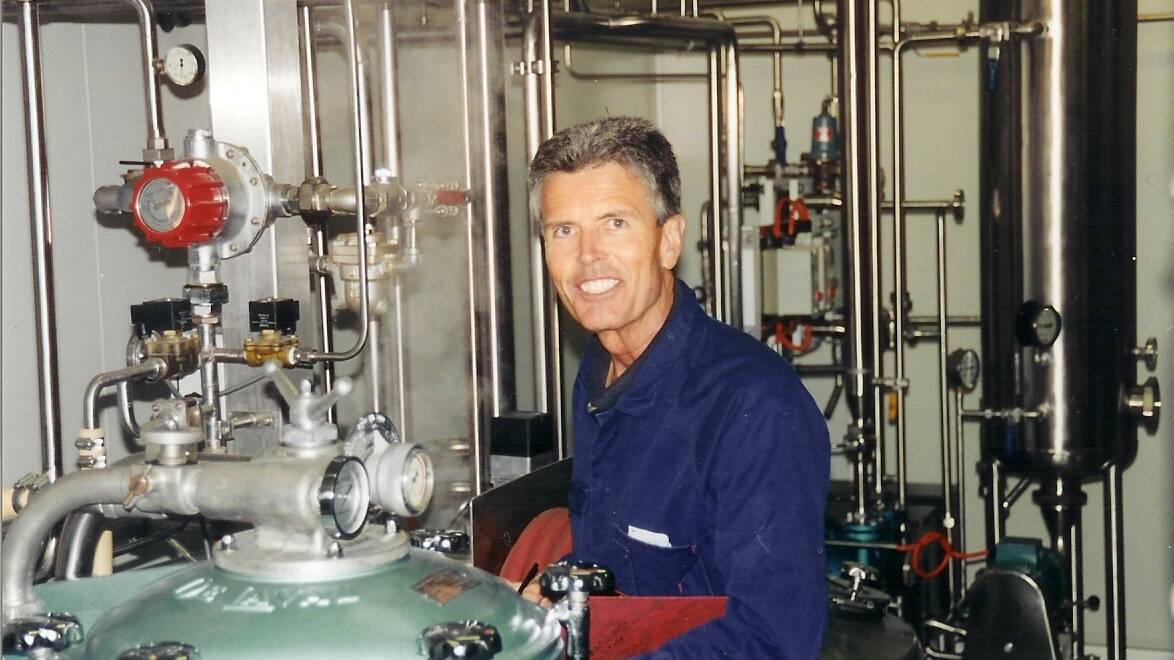

Niche Manuka and North Coast tea tree industries are too small to afford a research and marketing arm but they fought hard with limited resources to protect their future. Meanwhile, spare a thought for the Australian squalene industry – there’s only one bloke, Richard Saul, son of a North Coast prawn fisherman and world champion professional rower. For the past 24 years, Mr Saul has produced the rare oil in Melbourne, under the name Ocean Oils, distilling sustainably caught deep water shark liver oil to glean the stuff that is so precious in Asia.

Unlike tea tree oil and Manuka honey, squalene has no easy chemical marker that can pinpoint it to a specific location. As a result the market is now awash with imported squalene products claiming to be fair dinkum made in Australia when in fact none of it is coming from this regulated land.

Mr Saul can see that questionable, imported squalene from unsustainable fisheries and marketed and endorsed as Australian is destroying the country’s good name. Previous research uncovered fake squalene that contained sometimes very low levels of the real deal and in some cases a lot of linseed oil.

Dr Peter Nichols spent three decades researching marine oils with the CSIRO before retiring as an honorary fellow and says a regional fingerprint can be found in raw oil but once it is distilled and blended it’s anyone’s guess where it came from.

He says new base-line sampling is required for squalene analysis. That onus will likely fall on the individual shoulders of Mr Saul who has to defend his industry without much government intervention.

Meanwhile the Australian Made Campaign Ltd, as owner of the ‘Australian Made’ logo, currently endorses 64 different brands of purported ‘dinky die’ squalene despite concrete evidence that shows the oil is 100 per cent imported and is derived from unsustainable fisheries like Africa, India, Indonesia and the Philippines.

Adding insult to injury, Mr Saul says that despite years of lobbying for investigation of fake squalene, the ACCC has so far refused to act.

Typically, squalene is a highly refined distillate derived from the livers of certain deep-water dogfish sharks and has an enormous market in Asia where the natural product, in capsule form, is used for joint pain. Also there is some evidence to suggest its rapid oxidation can attract free radicals within the body, removing them from cancerous harm.

In the cosmetics industry, squalane (the hydrogenated form of squalene) is used as a moisturiser base because it is readily absorbed by the skin and is non-allergenic.

Mr Saul says the quality and purity of many of these so-called Australian brands of squalene is dubious, with the product often having poor aesthetics and rather fishy in taste and, more importantly, not sufficiently distilled and refined to properly remove the Dioxins, PCBs and organochlorines that are present in the livers of these top order predators.

Mr Saul says his quality process of double distillation purifies his squalene to 99.9 per cent and to do so involves a 20 per cent refining loss of product along the way; this critical point is of no interest to the fakers who are only chasing profit and who may not even be using squalene in their capsules.

Australian sourced raw materials used for the squalene oil are derived from by-catch dogfish species harvested from our sustainable and extremely well managed fish stocks in the world’s cleanest waters. Coupled with more than 24 years of expensive development with careful processing and rigorous refining, the Australian squalene has attracted a premium in the marketplace. And yet 100% of the bottles of squalene now sold at pharmacies and online and claiming to be made in Australia are actually not so and contain no Australian squalene whatsoever, says Mr Saul.

Mr Saul has been distilling shark liver oil for its Squalene content for the past 24 years and has navigated his business through tough times that saw Australian oil material availability fall from 150t/yr to 5t/yr in 2007 when the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA) closed 1.6 million square kilometres of ocean from Sydney to Cape Leeuwin to protect a few hundred square kilometres of Orange Roughy grounds. Deep-water dogfish species that have the good oil in their livers were by default included in that fishery ban. More recently, AFMA has slowly re-opened some deep-water fishing grounds after reassessing their sustainability and now Mr Saul can source about 50t/yr shark liver oil from the Australian fishermen. He is the only Australian producer to do so and is proud to utilise these once-discarded raw materials.